Press

OUTLAW BLUES - Larry Jon Wilson at

The 12 Bar Club, London, 15th July, 2008

By Robert Spellman, Thu, Jul 17, 2008

It’s a muggy July night on Denmark Street, London’s former Tin Pan Alley. The sky is low and movement is sluggish - swamp weather if you will, here in WC2.

In the tiny 12-Bar club, tucked away at the east end of this quiet strip off the Charing Cross Road, Larry Jon Wilson, a forgotten innovator of country’s so-called outlaw movement of the early 70s is to make a rare live appearance. Wilson’s ‘my way or the highway’ attitude to his craft has resulted in only five albums in about 40 years, so his touring, on the strength of this record at least, has been minimal. Even Stateside the Georgian is something of a cult figure - a reclusive, grandfatherly hipster who emanates warmth and mischief.

Yet few singers so broadly embody the south. From Larry’s acoustic comes a wondrous tangle of country, soul, blues and even funk. The specious divisions of genre fall away when big Larry pipes up.

Taking to the stage of this 17th century barn, one feels this cosily shabby venue could’ve been built for Wilson that afternoon. The stage is raised and the devout squeeze around the narrow spaces at the front and sides, gazing up at their hero - or anti-hero to be precise.

“My American dream fell apart at the seams,” Larry choruses on Heartland and the audience laughingly join in. Laughter, reflection and an irrepressible sense of loss hang heavy in the deep orange light this evening.

Shouts for faster numbers like Ohoopee River Bottomland and Sheldon Churchyard fall on deaf ears as the 68-year-old’s powerful hands dance over the fret board with feather-light grace, teasing out lost-love songs and memories and in that tender southern growl.

Majoring in chemistry, Wilson worked as a technical consultant for a fibreglass company but quit it all in 1973 to play his beautiful, mysterious songs. Why the sudden career change? What happened?

Maybe nothing. Maybe something as ordinary as heartbreak.

God bless him.

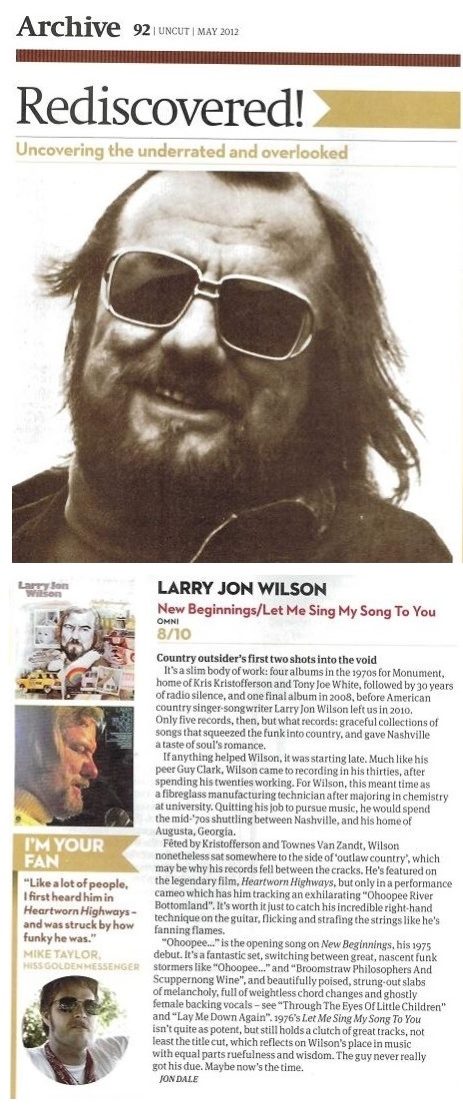

NOW I’M MAKING MUSIC (A Few Thoughts About Larry Jon Wilson)

Jefferson Ross Posted On September 8, 2010

It seems that everywhere I turn these days folks are eulogizing the music industry and what I think they’re doing, me included, is eulogizing their own hopes and dreams….the dream of the big hit, the cash bonanza, the big burrito full of cabbage. I even heard millionaire and legendary songwriting icon, Smokey Robinson, the other day on TV saying that we’ve gone back to ‘the era of the minstrel, where everyone is making music but no one is paying for it.’

So, in minstrel times like these, my thoughts turn to Larry Jon Wilson.

Now, here was guy who could write like an angel and sing like The Lord On High, a vivid and gifted storyteller who could mesmerize a crowd with just a few, simple words and leave you breathless and buzzing on his artistry. He was a salty and masterful guitar player and admired by the top professional musicians in Nashville and across the country. Yet, he never had a hit. Never enjoyed the big burrito.

In fact, after his record deal played out, he returned home to Augusta, worked a job and, for years, rarely performed at all. But even through all of that he still committed himself to excellence in his craft and his work…his gift. When he did return to the stage, we all laid palm fronds at his feet and declared him a legend but he usually only played very small venues and house concerts and waited nearly 30 years before making a modest ‘comeback’ album.

My new friend, Duke Lang, hung out with Mr. Wilson at The Mickey Newbury Gathering in Austin back in 2008, right before Larry Jon was to take the stage. They started talking about the biz and, I quote Mr. Lang here, “He said he would not have made any different choices if he could do it all again because he was simply incapable of being less than his complete, beyond-category self. And, he was deeply disgusted and saddened by how marginalized genuine artists had become in (American) society, but that it just wasn’t in him to stop sharing what gift he had. He went on and gave a remarkable, spontaneous, and spirit-fueled show, one I’ll always remember.”

So, here we are in 2010, staring at the new frontier of net marketing and sluggish sales and I really do feel hopeful that we can make a nice, boutique industry for ourselves. But right now, I’m not too concerned about that, really. I’m concerned about craft and joy and integrity of purpose…the thrill of moving an audience to tears and laughter.

I think that was Larry Jon’s secret. It was the song and the song was king.

One of my favorite Larry Jon Wilson quotes goes like this. He was being asked about his early days, shortly after college when he worked a very lucrative job in the textile business. He shucked all of that security and comfort to come to Nashville and begin his now famous struggle. He said he really enjoyed working for the textile industry and made a lot of great friends there. Wistfully, he looked off into the horizon and said, “Yeah, back then I was making money. Now I’m making music.”

I’m making music too. How about you?

Whatever happened to Larry Jon Wilson?

By Joel Oliphint

In 1975, a documentary filmmaker shot footage for what eventually became Heartworn Highways, a cult classic about country musicians who didn’t quite fit into the Nashville mold—folks like Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark, big names in the “outlaw country” movement that was just taking hold.

In one of the film’s opening scenes, a bearded, broad-shouldered musician in a Western shirt sits down with his guitar in a big Nashville studio and teaches his band how to play “Ohoopee River Bottomland,” a swampy, country-funk number about “a Georgia gator hole,” he says. He rhythmically slaps his guitar strings while singing in a strikingly smooth, Southern baritone. His talent jumps off the screen.

That man is Larry Jon Wilson, a name that, for most, doesn’t rank among the outlaw pantheon. By the time Heartworn Highways was released in 1981, Wilson had already begun to fade into obscurity.

But Jerry DeCicca, the singer/guitarist for Columbus band the Black Swans and a walking encyclopedia of American roots music, isn’t among those “most.” He and his UK musician/producer friend Jeb Loy Nichols were awestruck by that Heartworn Highways performance. They wanted to hear more. They managed to track down all four of Wilson’s old vinyl albums from the 1970s and were no less impressed.

Ultimately, the burning question in their minds was, “Whatever happened to Larry Jon Wilson?”

And then they set out to find the answer to that question.

Slipping through the cracks

Wilson, 68, calls himself a bullshitter. More accurately, he’s a storyteller, one who doesn’t take much prompting.

“I never learned nothin’ from a quiet man,” he says. In the course of a phone conversation, as he grills some rib-eye steaks in his hometown of Augusta, Ga., Wilson opines on everything from Greenwich Village coffeehouses and Akron’s Soap Box Derby to his friend Billy Joe Shaver, whom he calls “the best country-western writer ever.”

Wilson has called many musicians “friend” over the years, though he’s not one to name-drop. He ran with the likes of Waylon Jennings and a young Steve Earle, shared a farmhouse with his friend and touring mate Townes Van Zandt and considered legendary songwriter Mickey Newbury one of his best friends.

Wilson started his own musical journey later in life than most; he didn’t even own a guitar until UPS delivered one on his 30th birthday—the same day his father died, and the same day his wife found out she was pregnant with their first child. Needless to say, that 12-string Martin is not for sale.

“It’s like a talisman of that unusual weekend,” he says.

Just a few years later, Wilson made a demo tape. Monument Records—then one of the largest independent record companies in Nashville—liked what they heard and gave him a record deal. He recorded his first album, 1975’s New Beginnings, before ever meeting Monument’s now-legendary label boss Fred Foster.

But the transition to Music City wasn’t an easy one. Back in Georgia, he had a wife, three kids, a place in the suburbs and a good-paying job doing chemical research and development on polymers. He was good at it, and he enjoyed it. In most people’s eyes, he already had the good life.

“The choice I made was to give up the life of accumulating and calling it success, and to begin a life of creating and calling that success,” Wilson says.

Wilson would release four albums in four years on Monument, and even with the heavy-handed production that was common at the time, much of the material holds up well today—a singular sound that mixes country, funk, soul and pop.

“I liked his voice, and I liked his sense of detail,” says the Black Swans’ DeCicca. “I liked the fact that, lyrically, it’s really colorful stuff. There’s a sense of geography. You definitely feel like you’re in the South.”

“What also struck me is that it’s not macho,” he says. “It sounds rugged, but it’s really sentimental.”

DeCicca likes to say that Wilson is the only person he’s ever heard who actually sings with a Georgia accent. Nashville Songwriters Hall of Famer John Prine, a longtime Wilson fan, is similarly enamored with his singing.

“Larry Jon’s voice is one of the sweetest instruments I’ve ever heard,” Prine said via e-mail.

The problem was, no one quite knew how to market that unique sound. On the song “Throw My Hands Up,” Wilson laments, “Music City’s tryin’ to break me/They never knew how to take me.”

His refusal to conform didn’t further his career, either. He did things his own way, and he liked the fact that when he started out, he had a back-door key at Monument and could talk to Fred Foster whenever he felt like it. But things didn’t stay that way. Record companies like Monument began to be swallowed up by big, international conglomerates.

“I just didn’t want to be even a small contributing part to some company that has more people in its legal department than we had on our entire label,” he says.

“Larry Jon’s got a really good bullshit detector. He doesn’t want to deal with a bunch of suits,” DeCicca says. “Nobody wants to work with somebody who isn’t gonna play the game.”

Wilson never cared much about being famous, either. He had a first-hand view of fame, and wasn’t impressed by its effect. “It’s a sad thing when stardom ruins people’s motivation. I’ve never had that problem. I cannot be yesterday’s papers, because I was never today’s papers,” he says, laughing. “So there’s an upside to that.”

“But if I need a new engine in my car, I have to go do some distasteful gigs to get the money,” he says. “That’s one of the downsides.”

Wilson and Nashville soon parted ways. He wandered for a time around Florida Gulf towns and eventually settled back in Georgia. His marriage ended after 20 years. In addition to playing those occasional gigs, he has found work doing voiceovers and hosting a regional television program. He still opts for the newspaper over a computer or TV, and while he keeps in touch with some of his songwriter friends, many, like Van Zandt and Newbury, have passed away.

“There’s a lot of people that I think slipped through the cracks,” DeCicca says, “and he’s somebody that did.”

Lost and found

It didn’t take any great detective work to find Larry Jon Wilson. He’d continued gigging off and on in beer halls and whiskey bars in and around his Georgia home for years.

Jeb Loy Nichols, who makes his home in the UK, is a respected record producer there. Through contacts in the business, Nichols was able to reach Wilson. He had one question: “Could we get you to record again?”

Wilson was interested. Knowing his appreciation of Wilson’s music, Nichols brought his friend, DeCicca, into the picture and they began talking to Wilson about recording some new material.

“Larry Jon was open to the idea,” DeCicca says, “but it took a long time and a lot of different labels to come around.”

Eventually Nichols convinced Sony’s 1965 Records in the UK to put up money to record and release a new album. Nichols hired DeCicca to co-produce, DeCicca hired his friend Jake Housh of Columbus band Moviola to engineer, and in 2007 they rented a Ford Taurus and headed down to Perdido Key, Fla., one of Wilson’s old haunts, in hopes of recapturing the forgotten troubadour on record.

Perdido Key is a postcard-worthy barrier island that lies along the border of Florida and Alabama. The island’s beach community is home to spots like the Flora-Bama, a bar famous for its musical history (the Allman Brothers, John Prine and others have played there), its annual mullet-tossing contest and the Bushwacker, the bar’s best-known drink.

Perdido (“Lost” in Spanish) Key is also home to a condo complex called the Mirabella, where one of Wilson’s old friends offered up a picturesque 15th-floor suite overlooking the Gulf of Mexico as the makeshift studio setting for Larry Jon Wilson’s first album in almost 30 years.

It was a beautiful setting—for dinner and a drink. For recording, it was a bit unorthodox. And the recording process itself presented challenges.

Housh, who has recorded all of Moviola’s albums, was skeptical from the beginning. He didn’t think it would happen, even though it seemed like a great idea. “Record-type stuff notoriously falls through,” he says. “That someone would pay for us to go to Florida and do it sounded far-fetched.”

Much to his surprise, it was real, so Housh dropped everything and left. But when they arrived, something was missing.

“The first two days, (Larry Jon) wasn’t there,” Housh says. “We just holed up in a motel on the Florida-Alabama border for two days waiting for Larry Jon to arrive. I was about to wring Jerry’s neck.”

Wilson eventually arrived, his ruddy, craggy face still boasting that beard, albeit a much whiter one. Barrel-chested, his T-shirts and polos hang loose around a paunch common to men in their late 60s.

Unbeknownst to the production team, Wilson had a gig scheduled the day he arrived—his first of four over the next 10 days.

“They thought it was hilarious that the first day nothing happened,” says Housh, a family man who laughs now, but didn’t find it so funny then. “I was just like, ‘Guys, we can’t be down here dickin’ around.’”

Wilson, who was staying elsewhere in Perdido, sometimes showed up at the condo at 3 p.m., sometimes 10 p.m. There was no schedule, and even with the microphones set up and the computer recording, no one ever quite knew when a story would turn into a song, or even what song Wilson would play, much less if he intended to stay put. Housh eventually rearranged the condo’s pastel, flowered couches in an attempt to trap him behind the microphone.

Wilson explains the lackadaisical mood in Perdido Key in his charmingly aloof way: “I didn’t know we were doing an album,” he says. “We were just having a pretty nice time, and it became an album.”

There’s no disputing the good time, drinking Bushwackers at the Flora-Bama, eating at Triggers—a seafood restaurant with fresh grouper and fried cheesecake—and watching Wilson perform at hillbilly bars. He seemed to know somebody everywhere they went.

And despite—or, perhaps more accurately, because of—the carefree atmosphere, the album came out beautifully. Wilson’s deep, worn voice reverberates off the floor-to-ceiling windows and marble beneath his feet, and his rhythmic, funky guitar style has been supplanted by deft finger-picking that’s no less impressive and even more fitting to these songs, some of which are covers (Bob Dylan and Willie Nelson’s “Heartland,” Dave Loggins’s “Goodbye Eyes”). To capture the spontaneity of Wilson’s performances, DeCicca left in bits of Wilson’s banter before or after the songs.

“We wanted to do something that represented what Larry Jon does now,” DeCicca says. “We didn’t want it to be trendy.”

It’s an intimate record. You can hear Wilson’s inhales and exhales, the creak of his guitar. You’ll also hear some subtle fiddle, courtesy of Noel Sayre, the former Black Swans violinist who died in a swimming pool accident last summer. (Housh recorded Sayre’s parts separately at Used Kids Records.)

Most astounding is that all but one song on the record were first and only takes. Nichols and DeCicca, whom Housh calls two of the biggest music geeks he knows, would chat with Wilson about little-known singer-songwriters, alternate versions of songs and the like, and those conversations would spark songs—a result that DeCicca says wasn’t an accident.

“He saw my Paul Siebel CD,” DeCicca says, “and he goes, ‘Do you know Paul Siebel? I used to do his song about the whore.…’” Housh quickly hit “Record,” and that Siebel cover turned into an epic, three-song medley called “Whore Trilogy,” one of the album’s highlights.

“There was a point where we weren’t sure we were going to have enough for a record,” DeCicca says. “In the end, we did.”

Outlasting them all

The resulting album came out last year in the UK, and Tuesday will see its U.S. release on Drag City, home to artists such as Bonnie “Prince” Billy, Bill Callahan and the Silver Jews. Housh still can’t believe it, and DeCicca is overwhelmed by it all, too, going from a Larry Jon Wilson fan to a Larry Jon Wilson producer, all within a couple of years.

It’s probably not a rags-to-riches story, though. While Wilson is certainly getting more exposure to a new audience (he played a show with Steve Earle last weekend), it’s doubtful this album will bring him fame on the level of some of his contemporaries. And that’s just the way he likes it.

“I have singer-songwriter friends who went on to different things, and certainly, almost without exception, to what the world considers success,” Wilson says. “They probably feel bad for me, but they don’t realize I feel bad for them.… When I get around friends my age, it seems to have had more of a toll on them. I think it’s just because they may not have been as happy as I’ve been. They’re not as poor, either.”

“I’m enjoying playing more than I ever have, and I feel like I’m doing it well,” he says. “If you can’t beat the bastards, then the best thing to do is outlast them.”

Obituaries

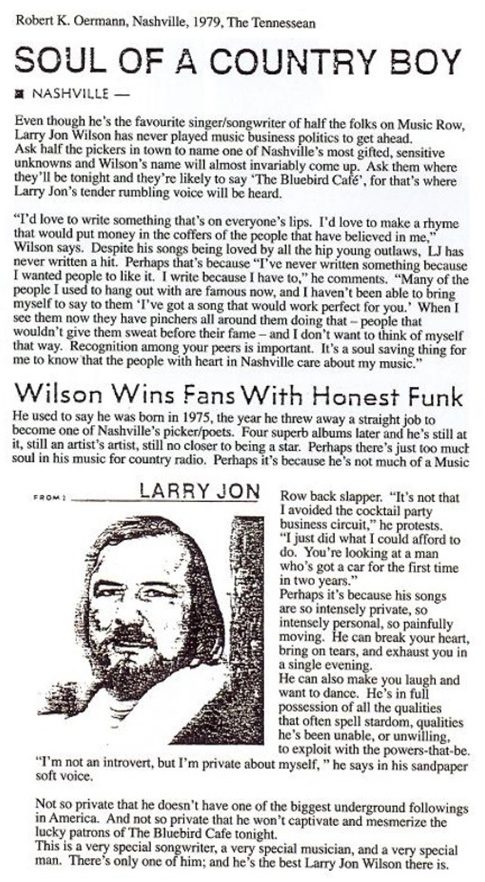

Songwriter Larry Jon Wilson was best known for his loose association with the 1970s Outlaw country music movement.

Singer traded 'company car life' to pursue music

Augusta-area singer, songwriter and practiced raconteur Larry Jon Wilson died Monday in Roanoke, Va.

Wilson, best known for his loose association with the Outlaw country music movement in the 1970s, gave up what he often referred to as the "company car life" to pursue music. His rumbling baritone and distinctive songwriting style, which combined elements of country, folk and Southern narrative, made him something of a musician's musician, garnering a coterie of friends and musical accomplices that included Townes Van Zandt, Mickey Newbury and Waylon Jennings.

The bulk of Wilson's recorded work - the albums New Beginnings, Let Me Sing My Song To You, Loose Change and The Sojourner - was released on the Monument Label. Last year, Wilson released his first new work in nearly 30 years, the self-titled Larry Jon Wilson, on the Chicago-based indie label Drag City. The release proved to be something of a career renaissance for Wilson, particularly in Europe, where he had maintained a small but fervent fan base.

"It has been nice," Wilson said in an interview in April. "It's been nice that, at this point in my life, people are interested."

In the long years between releases, Wilson kept busy with performances known for their intimate and improvisational nature, and doing voice-over work for television networks, including serving as the official voice for the Turner South network. A working definition of dichotomy, he was a public performer who valued his privacy. In his April interview, he acknowledged the irony of making his living onstage while allowing only a valued few access to his private life.

"I'm no introvert, but I am private," he said. "I like to say I find myself, quite often, alone in bad company."

Funeral arrangements have not been announced.

Larry Wilson Obituary

AUGUSTA, Ga. - Larry Jon Wilson of Augusta Georgia passed away June 21 in Roanoke, Virginia. The beloved singer/songwriter was preceded in death by his parents, John Tyler Wilson and Louise Phillips Wilson. He is survived by his four children Kimberly Jaye Wilson, Chatham Elise Wilson, Bertrand Tyler Wilson, Elizabeth Dalenberg; his grandchildren, Amanda Leigh Ham, Jamie Michelle Ham, Crystal Nicole Camden and Graham Tyler Wilson; his brother, Billy Joe Wilson; and his uncle, Dean Phillips. Larry Jon was signed as a writer and performer to Monument Records in Nashville, Tenn. He recorded multiple albums from 1975 to 2009 with several titles reaching the Top 10 charts nationally and internationally. His performances include many venues in the US and Europe including The Bitter End, Bluebird Cafe, The Great Southeast Music Hall, Frank Brown International Songwriter Festival and the London Summer Music Festival. He hosted and performed for a series of Georgia Backroads travel shows for the Georgia Public Broadcasting TV network (still being aired) and became the "voice" of the Turner South cable network announcing upcoming programs like Liars and Legends. His voice, wisdom and music will be missed by his family, friends and fans. A memorial service will be held on Sunday, June 27th, at 2:00 PM at The First Baptist Church of Augusta, Georgia, with interment in the church's memorial garden. Sign the guestbook at AugustaChronicle.com

Published by The Augusta Chronicle on Jun. 25, 2010

Larry Jon Wilson Obituary (by Jeb Loy Nichols)

My friend, the musician Larry Jon Wilson, who has died aged 71, was that rarest of things: an honest man in a profession built on glamour. A favourite of Nashville's leading singer-songwriters, from Willie Nelson to Kris Kristofferson and Will Oldham, he never achieved their commercial success. One of the first things he told me, in his sandpaper southern drawl, was: "Every time a record company comes calling, the buzzards start circling the house."

Larry Jon was born in Georgia and went to military school there: an experience, he said, that failed to damage him too severely. He attended the University of Georgia, and in the late 60s and early 70s lived in Florida. It was in the Coconut Grove neighbourhood of Miami, watching the singer-songwriter Fred Neil, that he decided to follow a career in music.

He liked to say he was born in 1975, the year he gave up his job selling boat varnish and landed in Nashville. He quickly became known as a singer and writer of intensely private, painfully moving tales of southern life. He signed to Monument Records and his first album, New Beginnings, proved a revelation among the hipsters and critics of Nashville.

When a film crew came to document country music's burgeoning "outlaw movement", they made straight for Larry Jon's door. The film Heartworn Highways (1981) featured his mesmerising performance of Ohoopee River Bottomland. During these years, Larry Jon and Townes van Zandt lived and toured together.

He made four records for Monument, each bearing his unique mix of country, folk and soul. Too funky for the country crowd, too heartfelt for pop radio, he fell between the cracks. "I never stopped," he told me, "I just downsized. Made my way to the Gulf coast and said forget it. I didn't want to be part of a business where lawyers earned more than the artists they represented."

In 2003, I put together a compilation entitled Country Got Soul for the London-based label Casual Records. Larry Jon's gothic funk song Sheldon Church Yard was the first track. In the album's liner notes, Kristofferson observed: "He can break your heart with a voice like a cannonball."

Larry Jon later played with the Country Soul Revue on the album Testifying. In 2007, 1965 Records finally convinced him to make a new record. I flew to Florida and spent 10 days in the capricious company of Larry Jon, listening to endless stories, driving around the sleepy back roads of Perdido Key and sitting on darkened porches watching the ocean. Occasionally, if we were lucky, we recorded a song or two.

The resulting self-titled CD, which I co-produced, was released in 2008 and collected a stack of five-star reviews. Larry Jon came to London that summer and played a series of sold-out shows. Among his admirers was Charlie Gillett. "Just when you think you've heard it all," he told me, "you hear Larry Jon."

He is survived by three children, Kimberley, Chatham and Tyler, from a marriage which ended in divorce; Elizabeth Dalenberg, whom he raised; his brother, Billy Joe; four grandchildren, Amanda, Jamie, Crystal and Graham; and his many fans.

Forgotten Outlaw Larry Jon Wilson: 1940-2010 (by Trigger Coroneos)

I’d love to tell you that I know a lot about Larry Jon Wilson, who died Monday at 69 from a stroke, but truth is I only know him through the bits of his music that have passed under my nose over the years, and from his appearance in the documentary Heartworn Highways. There isn’t a lot to be known about Wilson, because for nearly 30 years of his life, he wanted it that way.

Larry Jon Wilson is the textbook definition of a “Forgotten Outlaw.” His golden era is filled with songs and albums that are as entertaining and influential as anyone’s. Forgotten or not, Wilson was the complete package. He had the moxy and the taste for soul of Waylon Jennings. He had the songwriting, poetic prowess of Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark. He had deep, deep pipes that made Johnny Cash sound like a pre-pubescent. And he was a hell of a guitar player. Mix it all together and Larry Jon Wilson was an American original, whose due we can only hope will come posthumously, and whose legend deserves to eternally grow.

And he was an Outlaw plain and simple, maybe more so than most:

“Some people have used the ‘Outlaw’ tag effectively for a career move, but I don’t think ‘career move’ has ever entered my thinking. When I was in Nashville, we did the streets an awful long time, and we weren’t exactly holding prayer meetings. I loved my drinking days… I’m not ashamed of any of it.”

Born in Georgia, Wilson put out four relatively obscure, but critically acclaimed and loyally adored albums between 1975 and 1979 on the Monument imprint of CBS Records: New Beginnings (1975), Let Me Sing My Song to You (1976), Loose Change (1977), and The Sojourner (1979). If you find one of these albums in any format, buy it. They are as rare and highly sought after.

In 1980, Larry left the music business disillusioned after no real commercial success of any sort. His music just didn’t fit in any marketable scene. It was country, but with soulful, funky influences. Wilson’s music maybe was not influential to the outside world, but in the 70’s country Outlaw scene he was an artist the artists listened to. After 1980 he slipped into obscurity, doing voice-over work to pay the bills. Just last year he came out of the shadows to release Larry Jon Wilson which was beginning to spark new interest in his body of work.

Larry was also a champion of the very rare, but very coveted by true audiofiles song trilogy.

Larry Jon Wilson is one of the reasons savingcountrymusic.com exists, to make sure singular talents like this are not forgotten, and that our generation of talent doesn’t slip into obscurity like so many greats before. Do yourself a favor, skip on over to YouTube, ask around for his albums, and discover this artist. He’s one of those type of artists who you might say “name sound familiar,” but when you’re sat down and really exposed to him, all of a sudden a whole new world of music is opened up to you.

June 22, 2010

Songwriter Larry Jon Wilson died yesterday (6/21) at age 69. The Georgia native was recognized for his songs about rural life and for his association with contemporaries such as Townes Van Zandt, Mickey Newbury, Guy Clark, John Prine, and Kris Kristofferson.

Wilson didn’t start writing songs until age 30, but within a few years he had signed with a Nashville label and publisher. Monument released four of his records in the ‘70s (New Beginnings, Let Me Sing My Song To You, Loose Change, and Sojourner), but by the ‘80s he was disillusioned with the music business and returned to Augusta, GA.

Wilson’s career was mostly quiet for the next twenty-five years, but he still performed at listening rooms like Eddie’s Attic in Decatur, GA , the Bluebird Cafe in Nashville, and the Flora-Bama Lounge, in Perdido Key, FL. In recent years his music career saw a revival, spawning a new self-titled album, an overseas tour, and new fans.

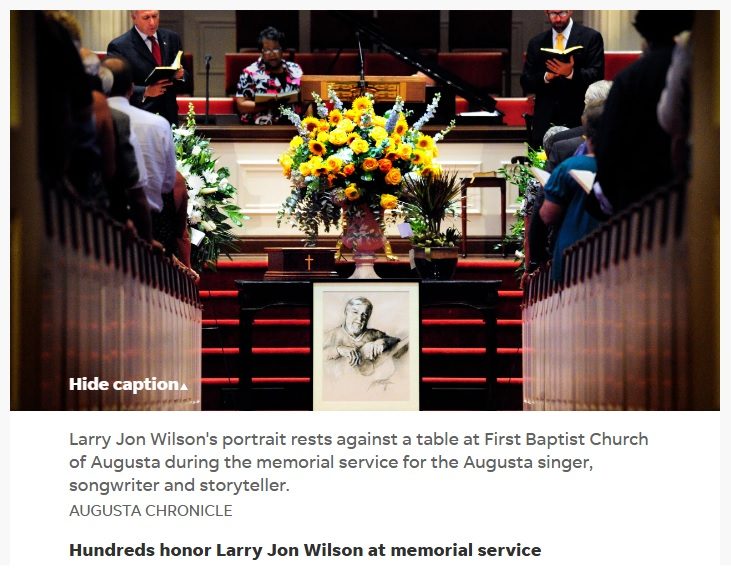

Hundreds honor Larry Jon Wilson at memorial service

A few hundred friends and family members gathered Sunday to remember Augusta music legend Larry Jon Wilson. Among them was the infant grandson Wilson was visiting in Roanoke, Va., when he suffered a stroke and later died on June 21 at age 69.

During a memorial service at First Baptist Church of Augusta, Tyler Wilson recalled asking his father what he needed as he lay sick in the hospital. "Dr. Kevorkian," said the singer, songwriter and storyteller, who made the Augusta area his home. It was typical Larry Jon, always using humor to lighten things up, his son said.

Musician friends, including Atlanta singer-songwriter Shawn Mullins, attended. Mullins, who performed an acclaimed series of shows with Wilson at Nashville's Bluebird Café a few years ago, said Wilson was like a father to him. Wilson was "a huge influence on me, and he was my hero," Mullins said. "He just meant the world to me, and his spirit and his music will live on. That's the beauty of what he did," he said.

Augusta musician George Croft, a friend of Wilson's since childhood, recalled running into Wilson at North Augusta's Sno-Cap drive-in a few months ago. "We talked about things to come," Croft said, "of memories, of Maryland Avenue and Wingfield Street." The pair, who played together as recently as two years ago for a Camp Rainbow benefit, grew up neighbors in Augusta, where Wilson's family moved when he was 4. "I thought Larry Jon Wilson would live forever," Croft said.

Wilson's surviving brother, Billy Joe Wilson, traveled from California for the memorial, which concluded with a soulful rendition of the gospel classic Farther Along, which Wilson recorded in 1976 on his second Monument Records album.

Other friends who paid their respects included Augusta photographer Jimmy Thomas, who shot the cover portrait for Wilson's first album; Michael Leonard, his manager when he signed with Monument; Bob Melton; Steve Brantley; and Mike Stewart.

"It was an extremely positive service from a lot of people who really cared about Larry Jon, and who he cared about," Augusta Chronicle music columnist Don Rhodes said.

Wilson's body was cremated and his ashes interred at First Baptist's memorial garden.

Friends of Larry Jon's

Larry Jon's songs

by other artists

Billy Strings covers Larry Jon's Broomstraw Philosophers and Scuppernong Wine in concert

ERIN THOMAS covers Larry Jon's New Beginnings (Russian River Rainbow)

Whiskey Foxtrot cover Larry Jon's Ohoopee River Bottomland on The Waughtown Tapes, Vol. 1, 2018

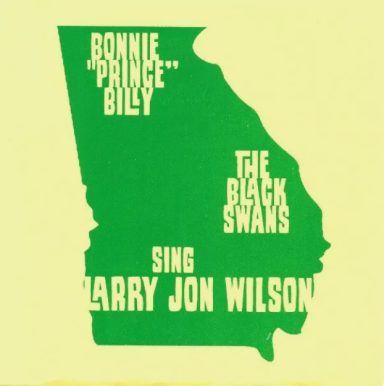

Bonnie Prince Billy & The Black Swans

Many are still mourning the passing of immensely talented and woefully overlooked country singer Larry Jon Wilson. But to celebrate his music, Bonnie “Prince” Billy and Columbus’s the Black Swans “Sing Larry Jon Wilson” on this new Drag City seven-inch. The Bonnie Prince, with some help from Cheyenne Mize, tackles “Bertrand My Son” off Wilson’s 1975 Monument Records debut New Beginnings. Jerry DeCicca, who produced LJW’s self-titled “comeback” album released on Drag City last year (my fav of ’09), enlisted his Black Swans to do “The Man I Wish For You,” an unreleased song that DeCicca says he found “rotting away on a reel-to-reel in the EMI basement in Nashville.” (Drummer/Orchestraville alum Keith Hanlon recorded the session at the Grandview Heights Public Library.)

LJW is a particularly difficult artist to cover. His rich, Georgia baritone and singular guitar style gave all his songs an inimitable feel, and any songs he covered became Wilsonized so much that you’d think they were his songs all along. These two tracks succeed in much the same way while still paying homage and communicating a reverence to a man DeCicca and Oldham revered.

Artwork was screenprinted by Nick Nocera of Alison Rose. In Columbus, you can find several copies for $7 apiece at Yeah, Me Too coffee in Clintonville; the rest of the world will have to wait till Sept. 21 when Drag City will exclusively handle distro.

Long live Larry Jon Wilson.

Interview by Mike Escoto with Jerry DeCicca, The Black Swans for phoenixnewtimes.com - Jan. 10, 2011

UOTS: Another project you worked on recently was a split 7" with Bonnie "Prince" Billy called Sing Larry Jon Wilson. You also did some producing work with him. How did you first get exposed to Larry Jon Wilson's music?

JD: The first time I ever heard him he was in that film Heartworn Highways which I saw in probably like the mid '90s or something. He was only in it for maybe a couple of minutes and then I saw his records at a record store in Nashville and when I saw those I got those. Then I got to meet him because he was part of this group of other guys like Dan Penn and Tony Joe White, Donny Fritts, Billy Swan, that were sort of modeled after the Buena Vista Social Club or something like that but were like a bunch of older guys from the south in Dan Penn's basement and cutting one or two songs each and it was called Testify and I got hired to write the liner notes for that. So I got to go down there and then meet him at that point in Nashville and got to hang out with him for a couple of days. So that's kinda what started it and that's how I met him and then it was for the next three years having phone conversations and driving from Ohio to Nashville for his gigs.

Swedish Metall band HORISONT covers Larry Jon's Sheldon Churchyard

"As big fans of country music we wanted to do a couple of songs that people might not expect from us. Still, we wanted them to sound like Horisont. So we set up at Let Them Swing Studio and hit the record button just to see where the songs took us. This is the result."

Contact

If you want to contact us, just use the message board here to the right.

And if you have any material from Larry Jon's performances, be it video, audio or pictures, and think it should be shared with the world, we will happy to help either on this website or on the youtube channel https://www.youtube.com/@WilsonizerLJ

We are not making any money from this project, but just want to keep Larry Jon's music and memory alive.

Wir benötigen Ihre Zustimmung zum Laden der Übersetzungen

Wir nutzen einen Drittanbieter-Service, um den Inhalt der Website zu übersetzen, der möglicherweise Daten über Ihre Aktivitäten sammelt. Bitte überprüfen Sie die Details in der Datenschutzerklärung und akzeptieren Sie den Dienst, um die Übersetzungen zu sehen.